I was insulted, truly. I enjoy yoga on occasion. It is amazing how flexible it can make you with regular practice, and I could not figure out why anyone would say yoga and running do not mix.

Not until reading "Runner's Body" (RB).

http://www.rwrunnersbody.com/uof/rwrunnersbody/?keycode=097308

Let me clarify the bomb dropped in BTR ... yoga, and especially extreme yoga, may not be the best for a long distance runner trying to increase speed and/or distance. It is the breakdown of energy use that RB pinpoints, and how joint health and mobility impacts running.

To start out, let me give you a little anatomy lesson: there are three stabilizing factors involved with all moveable joints: the shape of the bone tips that move together and create the joint (think elbow, knee, hip, etc), the ligaments that wrap around the joint (think about a twisted ankle and the swelling involved), and the muscles that reinforce and surround that same joint (think about how much stronger you get doing planks, almost pure muscle work).

The articulating surfaces of the shoulder joint are the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula.

The articulating surfaces of the knee joint are primarily the distal head, or condyles, of the femur and the proximal head, or condyles, of the tibia.

It may be a bit easier to picture in this flexed knee picture, where the condyles of the femur (covered in protective cartilage) are very easy to see.

The articulating surfaces of the hip joint are made up of the deep socket of the pelvis, the acetabulum, and the ball of the femur that fits rather neatly (usually) into the acetabulum.

For the most part, we cannot do much about the bone tip shape (it is genetically programmed) and generally holds us in good stead unless disease, such as arthritis, causes the shape to change. Some of our joints have a shape that lock it out at certain extension angles (fingers, elbow), while other joints allow a remarkable range of motion (shoulders, hips).

Ligaments attach bone to bone, and stabilize joints. The shoulder joint is fairly shallow as far as the bone structure is concerned, and therefore the ligaments have a very important job in stabilizing the shoulder joint. If you ever pop the shoulder out of joint, you stretch the ligaments, which cannot return to their original, pre-stretched state. It is that much easier to pop the joint out of place next time.

The knee joint is heavily surrounded by ligaments that do their best to stabilize this strange joint (our patella is such an interesting evolutionary adaptation IMO). There are, in fact, three bones involved in ligamental attachment: femur, tibia, and fibula.

This hip joint is also a "ball and socket" like the shoulder. However, it is much more stable due to the depth of the acetabulum (much deeper than the glenoid cavity). So the ligaments do not have to work quite as hard to keep the joint stable in the hip as they do in the shoulder.

Much like the articulating surfaces, we cannot do much to "strengthen" our ligaments, but we can stretch them out. With age and injury, we replace damaged tissue with scar tissue, which is remarkably strong, but with little stretch. So we need to be careful of our ligaments, stressing them enough, but not too much.

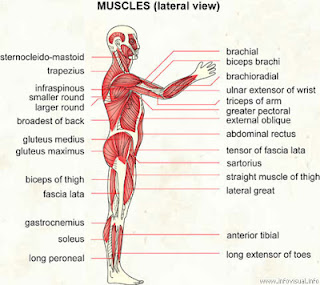

Our musculature is kind of like the layers of an onion. The smaller muscles are in towards the center (usually) while the larger muscles wrap around the entire structure on the outside. The three above photos show the superficial human musculature, and generally the biggest and strongest muscles.

These two pictures are some of the deeper muscles that stabilize the shoulder, they are much smaller than the superficial muscles. It is the smaller muscles that are easy to damage, and damage badly, because we have other muscles that can compensate.

Finally we come to the root of the problem, musculature of the joint. We can strengthen muscles quite easily. Though again, like the ligaments, we want to push just hard enough, but not too hard. We can also stretch muscles. And this is what yoga does, it takes someone who has a set amount of flexibility and increases that flexibility, often by stretching the muscle (and to some extent the tendon that attaches that muscle to the bone).

This is the rub. How many flexible runner's do you know? Many runner's I've seen are, in fact, extremely inflexible. Their joints have a very limited range of movement. Have those runner's take a couple yoga classes, and their joints gain greater flexibility.

However, this very flexibility slows a runner down, and it all has to do with energy expenditure. Once the joint gains greater flexibility, the muscles have to work harder to keep the joint within a certain range of motion in running. By the muscles performing extra work in joint stabilization, there is less energy available for distance and speed.

Is it going to have an impact on most runners? I doubt it will be noticeable.

Is this going to up your injury likelihood? No, I do not think so. (However ... you can injure yourself in yoga by pushing your joints too far just like you can injure yourself in running by pushing yourself beyond your limits.)

Regular yoga for a runner does mean you will not be able to go as far as fast.

Think of it as multitasking ... before yoga, the runner's joint could only do one thing, run. After yoga, the joint is more flexible, and can handle a greater number of tasks. But, it may not be able to do any one task exceptionally well.

I see runner's having several yoga options with this insight: 1) stop asking your joints to multitask, i.e. give up yoga, 2) stop worrying about the loss of a couple seconds in a run, i.e. enjoy all aspects of yoga, or 3) stop asking your main running joints to multitask, i.e. do not deeply stretch the hips and knees.

If you want to be a well rounded athlete, I think options 2 or 3 are the best. If you are experiencing massive time loss after all those hip opening exercises, don't push your hip joints so much, let them stay a little stiffer. Work on upper body strength exercises, instead.

If you are trying to shave time off your PR in marathon, or "in the running" (ha, ha) for an Olympic medal, perhaps you would do better with option 1.

2 comments:

Great post...I know I'm a year late in commenting :-). I actually quit running for yoga. I don't think yoga is necessarily bad for runners, but I think for yoga practitioners (whose goal is to do very advanced asanas), running is bad.

As a yoga practitioner, I wanted to do things like put my legs behind my head or intense backbends where my feet are on my head. Had I continued running, I doubt these postures would've been attainable. However, I miss the high of running sometimes...it just isn't the same adrenaline rush from yoga.

Of course, the goals in and of themselves of the two vary slightly. I think both athletes and yogis would argue that the two help create a greater peace of mind.

Happy running!!xx

Best,

Tiffany

There is a new kind of yoga called YogAlign based on doing functional body positions that improve posture. A runner with great alignment will run faster and have less long and short term injuries. Yogalign does not stretch your ligaments and does improve breathing capacity. So I agree that yoga might not be great for runners which is why I created YogAlign, a pain-free yoga style that does not require any toe touching or uncomfortable positions. Also about traditional yoga, not only does having looser ligaments require more muscle actions, but laxity destabilizes joints and leads to many serious joint problems.

Post a Comment